(Disclosure: I received a review copy of this beauty.*)

Not only do I have a scrumptious picture book to talk about, I also had the added pleasure of chatting with the makers of this delight.

Brothers Jon and Tucker Nichols not only made Crabtree (their debut picture book) together, but they both wrote and illustrated it. Yes. It reads like the creation of one genius mind. But it’s actually two. Published by the wonderful McSweeney’s McMullens, this book is a work of art that I’ve been tempted to cut up and paste all over my ceiling to just lie down and stare at. Luckily to avoid such sacrilege, they very thoughtfully created a dust jacket that opens out to a giant poster you can pin up. See? They really did think of everything.

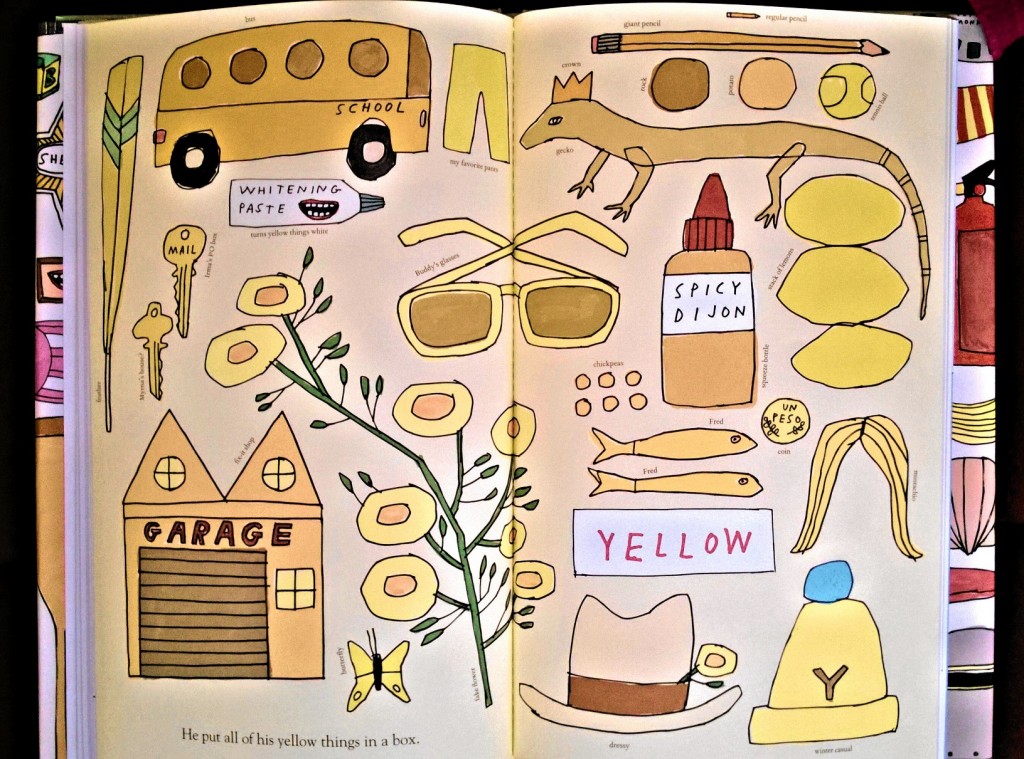

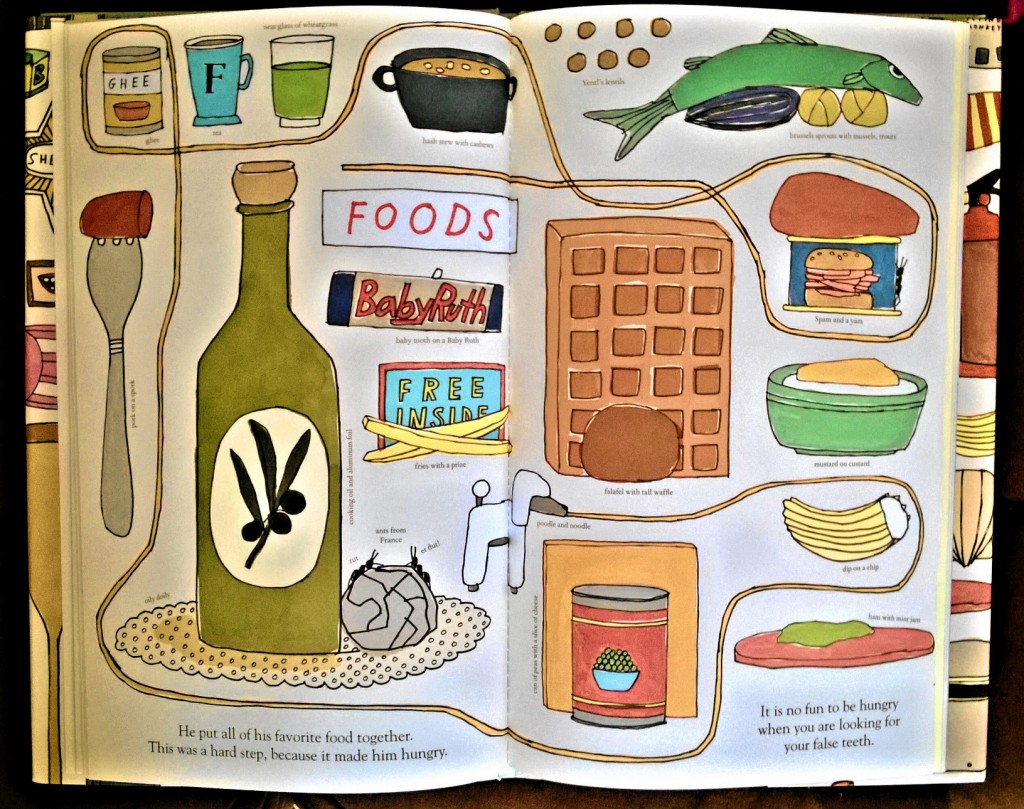

Crabtree is named after its protagonist, Alfred Crabtree — a man who wakes up to realize that his false teeth are missing. And in his quest to find them, he begins to search through all of his belongings. The task starts to become significantly more arduous because of all the things he’s accumulated, and Alfred soon organizes them along the way to make it a less stressful exercise. Almost the entire book is a quirky visual catalogue of everything Alfred owns. As you flip through the pages, you’ll find yourself chuckling at witty text and strange objects (and probably wondering why you don’t also have duck decoys and giant pencils. I mean, why don’t you?)

Jon & Tucker Nichols

I love the narrative structure of this book. Within its outer framework of the quest-for-the-missing-teeth, there are so many other paths you can go down. I want to say it’s like a puzzle, but actually its not. With a puzzle you’re fitting pieces together to make one larger entity, but in Crabtree it’s like you’re being given a piece to a different puzzle each time. It’s a story full of other potential stories; a tree with many, many branches. And at its core, it’s almost a meditation on the relationship between people and their belongings. What defines us? How much of the things we own are part of our identity? As you go through the book, you begin to experience it on multiple levels — it’s far more than the things you see on the page. Although, the things on the page will have you cackling throughout too; bonus! It’s hard to be both hilarious and deep, and this book achieves both effortlessly. To me, Crabtree is like the ultimate map to everywhere. Without any directions. Intriguing, indeed.

Jon & Tucker Nichols

When Crabtree was published, editor Brian McMullen shared this must-read conversation he had with the creators about their collaborative project. Apart from being completely entertaining, it’s also very informative and insightful. Lucky for me, Jon and Tucker were willing to subject themselves to a picture book related Q&A session as well…

Gayathri: I’ve honestly lost track of how many times I’ve re-visited Crabtree. It’s like a board game that’s got excellent replayability. Which picture books that you’ve come across have kept you coming back for more? And, why?

Jon: Thanks Gayathri! That aspect was really important to us. We really wanted to make a picture book that didn’t get depleted after a few visits. I don’t think there’s just one way to do that. Books I revisit are pretty different from each other. I come back for the poetry, for the visual worlds, for the sense of timing, for characters. The one thing that is sure to keep a book from drawing me back is a straight up moral lesson. I like a book that makes me do more work than that.

Tucker: It seems like most of the books I want to read more than a few times with my daughter have been around for a long time. Likewise with board games. Not sure if that means people used to be better at making these things, or maybe time just filters out the lame ones. (I stayed at a cabin in the mountains recently where they had some old, virtually unplayable board games, so they didn’t get them all right.)

Giant Jam Sandwich by John Vernon Lord

A Very Special House by Ruth Krauss and Maurice Sendak

The Three Robbers and Crictor by Tomi Ungerer

I Am a Bunny by Richard Scarry

Blueberries for Sal by Robert McCloskey

Ferdinand by Munro Leaf and Robert Lawson

Little Bear original books by Else Holmelund Minarik illustrated by Maurice Sendak

Curious George Rides A Bike by H.A. ReyG: As far as the creative process, being author-illustrators, how did you approach making a picture book? Did the story come first? Or did, say a doodle of a duck, inspire the entire narrative?J: The story definitely did not come first. In a way, the story kind of came last. This was an absurd and inefficient way of making a book, and it’s a hard process to recommend, but it’s how it went down. We started with an idea. An idea that wasn’t so much a story as a situation. Things and the way they’re organized. As we thought that through, we began to see the outlines of a character. The whole thing started to click into place when we found ourselves using the objects in the book to describe their owner. The storyline was something we wanted to keep fairly subservient to that basic vision, and it developed slowly, after we’d hammered out who this Crabtree fellow was and what he had laying around his house.

T: We aren’t known for our systems or linear thinking. We are maybe better known for our noodling. In this case, with McSweeney’s help, we noodled until we had a full book. Not sure any other publishing house has such a high tolerance for noodling.

G: I adore the illustrations in this book; they really give it a handcrafted feel. Do you both inherently have similar drawing styles, or did you mutually decide on an aesthetic for Crabtree?

J: I think we have similar aesthetics, similar sensibilities. We both really like lines. But Tucker’s a really accomplished artist who gets at something way beyond cartooning in his work. I’m considerably more limited. I was very happy that our styles came together so well in this.

T: For people who are curious, Jon drew all of the people and portraits and I drew all of the objects. That too was less about assigning roles and more just taking to the things we naturally do. Jon has a thing for people. Although he does draw some pretty amazing dogs too. And alligators. He also plays music on a thousand different instruments, which is a thousand more than I can.

G: From the large-format size and page fold-outs to the dust jacket-that-turns-into-a-poster, Crabtree really celebrates the printed page. In terms of physical format, what is/are the most imaginatively constructed picture book(s) you’ve seen?

J: From the beginning, we were working with a real master of the form. Brian McMullen, our editor, has the kind of love of great picture books that you don’t see very often. We all agreed that we were simply going to shoot for the most fun book to hold in your hands that we could dream up. In fact, if it’s great picture books you’re looking for, you couldn’t do much better than what McSweeney’s McMullens has been putting out under his leadership. Besides those, it’s hard not to love Joelle Jolivet‘s huge books, Maira Kalman‘s books… plenty of others.

T: For sheer mindbogglingness, it’s hard to beat Chris Ware. Also Mitsumasa Anno somehow creates density and wonder and quiet in his books. There are so many good ones out there though.

G: Any more picture book goodness we can look forward to seeing from you both? Either collaborative or independent projects? Please say yes!

J: You’re sweet. We’re hoping we can carve out the time to do something else soon. We have a lot of ideas and we love working together.

T: I think we are just getting started. We are in no rush but we are already talking about what happens to Alfred when he gets back from vacation.

Can. Hardly. Wait.

I’d like to thank Jon and Tucker for taking the time to answer my questions. It’s refreshing to get such involved, thoughtful and amusing responses. As for Crabtree, it’s dangerously addictive. Don’t say you hadn’t been warned.